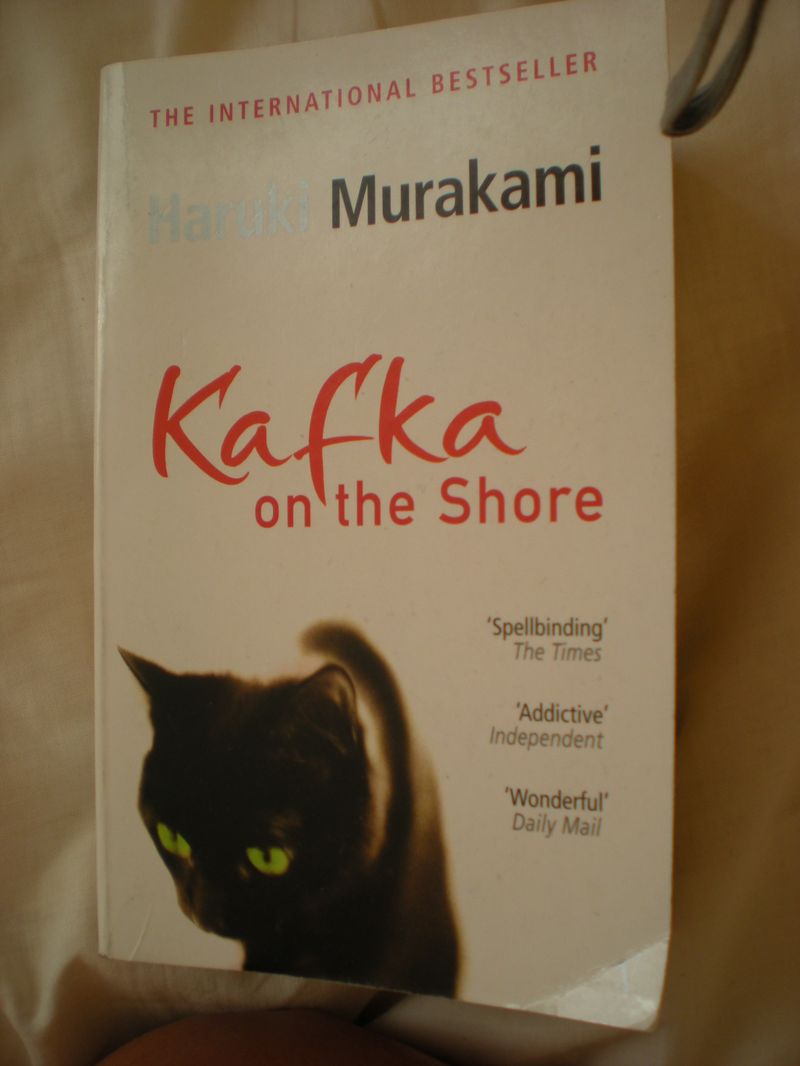

Haruki Murakami – Kafka on the Shore

Den var bra. Fin stämning, och allt det där. Men Norwegian Woods var bättre.

”My mobile-phone number,” she says with a wry expression. “I’m staying at my friends place for a while, but if you ever feel like seeing somebody, give me a call. We can go out for a bite or whatever. Don’t be a stranger, OK? ‘Even chance meetings’… how does the rest of that go?”

“’Are the result of karma’.”

“Right, right,” she says. “But what does it mean?”

“That things in life are fated by our previous lives. That even in the smallest events there’s no such thing as coincidence.” (39)

“In ancient times people weren’t simply male or female, but one of three types: male/male, male/female or female/female. In other words each person was made out of the components of two people. Everyone was happy with this arrangement and never really gave it much thought. But then God took a knife and cut everyone in half, right down the middle. So after that the world was divided just into male and female, the upshot being that people spend their time running around trying to locate their missing other half.” (48/49)

All I know is I’m totally alone. All alone in an unfamiliar place, like some solitary explorer who’s lost his compass and his map. Is this what it means to be free? (56)

“[…] It’s as Goethe said: everything’s a metaphor.” (139)

“Good question,” Oshima says, and pauses as music fills in the silence. “ I have no great explanation for it, but one thing I can say: works that have a certain imperfection to them have an appeal for that very reason – or at least they appeal to certain types of people. Just like you’re attracted to Soseki’s The Miner. There’s something in it that draws you in, more than more fully realised novels like Kokoro or Sanshiro. You discover something about that work that tugs at your heart – or maybe we should say that the work discovers you. Schubert’s Sonata in D Major is like that.” (144)

Epitome (146)

It’s all a question of imagination. Our responsibility begins with the power to imagine. It’s just as Yeats said: In dreams begin responsibility. Turn this on its head and you could say that where there’s no power to imagine, no responsibility can arise. Just as we see with Eichmann. (172)

“But Kafka isn’t my real name. Tamura is, though.

”“But you chose it, right?”

I nod. I’d decided a long time ago that this was the right name for the new me.

“That’s the point, I’d say,” Oshima says. (208)

“[…] As long as you have the courage to admit mistakes, things can be turned around. But intolerant, narrow minds with no imagination are like parasites that transform the host, change form and continue to thrive. They’re a lost cause, and I don’t want anyone like that coming in here.” (240)

“It was the ancient Mesopotamians. They pulled out animal intestines – sometimes human intestines, I expect – and used the shape to predict the future. They admired the complex shape of intestines. So the prototype for labyrinths is, in a word, guts. Which means that the principle for the labyrinth is inside you. And that correlates to the labyrinth outside.” (460)